Demetrius III Eucaerus

| Demetrius III Eucaerus | |

|---|---|

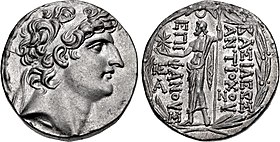

Demetrius III's portrait on the obverse of a tetradrachm | |

| King of Syria | |

| Reign | 96–87 BC |

| Predecessors | Antiochus VIII, Antiochus IX |

| Successors | Philip I, Antiochus XII |

| Contenders |

|

| Born | between 124 and 109 BC |

| Died | after 87 BC |

| Dynasty | Seleucid |

| Father | Antiochus VIII |

| Mother | Tryphaena |

Demetrius III Theos Philopator Soter Philometor Euergetes Callinicus (Ancient Greek: Δημήτριος θεός Φιλοπάτωρ σωτήρ Φιλομήτωρ Εὐεργέτης Καλλίνικος, surnamed Eucaerus; between 124 and 109 BC – after 87 BC) was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the King of Syria between 96 and 87 BC. He was a son of Antiochus VIII and, most likely, his Egyptian wife Tryphaena. Demetrius III's early life was spent in a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII in 96 BC. After the death of their father, Demetrius III took control of Damascus while his brother Seleucus VI prepared for war against Antiochus IX, who occupied the Syrian capital Antioch.

The civil war dragged on; Seleucus VI eliminated his uncle, whose heir Antiochus X counterattacked and drove Seleucus VI to his death. Then the twins Antiochus XI and Philip I, brothers of Demetrius III, attempted to avenge Seleucus VI; it ended with the death of Antiochus XI and the interference of Demetrius III on the side of Philip I in a war against Antiochus X that probably lasted until 88 BC. In 89 BC, Demetrius III invaded Judaea and crushed the forces of its king, Alexander Jannaeus; his near victory was cut short by the death of Antiochus X. Demetrius III rushed to Antioch before Philip I could take advantage of the power vacuum and strengthen his position relative to Demetrius III.

By 87 BC, Demetrius III had most of Syria under his authority. He attempted to appease the public by promoting the importance of the local Semitic gods, and he may have given Damascus the dynastic name Demetrias. By late 87 BC, Demetrius III attacked Philip I in the city of Beroea, where Philip I's allies called on the Parthians for help. The allied forces routed Demetrius III and besieged him in his camp; he was forced to surrender and spent the rest of his life in exile in Parthia. Philip I took Antioch, while Antiochus XII, another brother of Demetrius III, took Damascus.

Background, family and early life

[edit]

The Seleucid Empire, based in Syria, disintegrated in the second century BC as a result of dynastic feuds and Egyptian interference.[1][2] A long civil war caused the nation to fragment as pretenders from the royal family fought for the throne.[3][4] This lasted until about 123 BC, when Antiochus VIII provided a degree of stability which lasted for a decade.[5] To maintain a degree of peace, Egypt and Syria attempted dynastic marriages,[6] which helped Egypt destabilise Syria by supporting one candidate to the throne over another.[3] In 124 BC, the Egyptian princess Tryphaena was married to Antiochus VIII.[7] Five sons were born to the couple: Seleucus VI, the twins Antiochus XI and Philip I, Demetrius III and Antiochus XII.[note 1][9]

In 113 BC, Antiochus VIII's half-brother Antiochus IX declared himself king; the siblings fought relentlessly for a decade and a half.[5] Antiochus IX killed Tryphaena in 109 BC.[10] Antiochus VIII was assassinated in 96 BC;[11] this date is deduced from the statement of the first century historian Josephus, who wrote that Antiochus VIII, who assumed the throne in 125 BC, ruled for twenty-nine years, and is corroborated by the third century historian Porphyry, who gave the Seleucid year (SE) 216 (97/96 BC) for Antiochus VIII's death.[note 2][13] Following the death of his brother, Antiochus IX took the Syrian capital, Antioch,[14] while Seleucus VI, established in Cilicia, prepared for war against his uncle.[15] In modern literature, Seleucus VI is considered the eldest son,[note 3][17] and Demetrius III is considered younger than Antiochus XI and Philip I.[18] However, almost nothing is known about the early life of Demetrius III, who might have been the eldest son himself.[17] According to Josephus, before assuming the throne, Demetrius III lived in the city of Knidos.[17]

Reign

[edit]Antiochus IX did not take Damascus following the death of his brother; he was probably focused on the threat of Seleucus VI and could not spare the resources for an occupation of Damascus. This eased Demetrius III's elevation to the throne; he took Damascus in 96 BC.[19] The earliest coins struck in the name of Demetrius were produced in Damascus in 216 SE (97/96 BC);[20] only one Damascene obverse die is known from 216 SE (97/96 BC), indicating that Demetrius's reign started late that year, giving him little time to produce more dies.[21] The only ancient works of literature dealing with Demetrius III's career are those of Josephus and the Pesher Nahum, a sectarian commentary on the Book of Nahum.[22] Historian Kay Ehling noted that Josephus's account is a condensed summary and the actual course of events surrounding Demetrius III's seizure of power needs to be reconstructed.[23] Thus, interpreting the numismatic evidence is instrumental for the problematic chronological reconstruction of Demetrius III's reign.[24]

Name and royal titulary

[edit]Demetrius (translit. Demetrios) is a Greek name that means "belonging to Demeter", the Greek goddess of fertility.[25] Seleucid kings were mostly named Seleucus and Antiochus; "Demetrius" was used by the Antigonid dynasty of Macedonia as a royal name, and its use by the Seleucids, who had Antigonid descent, probably signified that they were heirs of the latter.[26] Hellenistic kings did not use regnal numbers, which is a modern practice; instead, they used epithets to distinguish themselves from similarly named monarchs.[27][28] Demetrius III's most used epithets are Theos (divine), Philopator (father loving) and Soter (saviour);[29] the aforementioned epithets appear together on all his Damascene and Antiochene coins.[30][31] In Cilicia, two epithets were used in conjunction: Philometor (mother-loving) and Euergetes (benefactor).[31] The coins from Seleucia Pieria bear three epithets together: the ones appearing on the coins of Cilicia, combined with the epithet Callinicus (nobly victorious).[32] Theos Philopator Soter served to emphasise Demetrius III's descent from the line of his grandfather Demetrius II who bore the epithet Theos; Soter was an epithet of Demetrius III's great-grandfather Demetrius I,[note 4] while Philopator represented his devotion to his deceased father Antiochus VIII.[34] With Philometor, Demetrius III probably sought to emphasise his Ptolemaic royal Egyptian descent through his mother Tryphaena.[35]

Eucaerus is a popular nickname used by the majority of modern historians to denote Demetrius III, but it is a mistranscription of the nickname given by Josephus in his works The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews. The earliest Greek manuscripts of Josephus's works contain the nickname Akairos in three places. Eucaerus appeared as a later development, and is attested in the Latin versions of the manuscripts.[note 5][38] It was probably a copyist, thinking that Akairos was a mistake and trying to correct it, that led to the appearance of Eucaerus.[37] Eucaerus translates to "well-timed", while Akairos means "the untimely one".[39] Josephus did not explain the origin of Akairos.[40] Such popular nicknames are never found on coins, but are handed down only through ancient literature;[41] neither Eucaerus or Akairos was used by Demetrius III on his coinage.[42] Josephus is the only source for the nickname; in the view of historians David Levenson and Thomas Martin, Eucaerus should not be used to refer to Demetrius; instead, Akairos, or one of his official epithets should be used.[38]

Manner of succession

[edit]According to Josephus, Tryphaena's brother Ptolemy IX of Egypt installed Demetrius III in Damascus following the death of Antiochus XI Epiphanes in 93 BC; this statement cannot be correct as the date given by Josephus contradicts the numismatic evidence from Damascus.[20] Despite the chronological error, several arguments justify the theory of a collaboration between Ptolemy IX and Demetrius III;[43] according to Ehling, the assumption of the epithet Philometor (mother loving) was meant to highlight Demetrius III's relation to his uncle Ptolemy IX.[35] Two main reconstructions of Demetrius III's rise to power exist:

- Demetrius III started his reign in Damascus: the numismatist Oliver Hoover viewed the ascendance of Demetrius III in the context of the war of sceptres, a military conflict between Ptolemy IX and his mother Cleopatra III, who was allied with Alexander Jannaeus of Judaea. This war took place in Coele-Syria and ended in 101 BC; Ptolemy IX was defeated and retreated to Cyprus. However, Hoover noted that Josephus synchronised the retreat of Ptolemy IX with the death of Antiochus VIII in 97/96 BC; such a synchronisation is perceived as imprecise by many scholars, but Hoover suggested that Josephus consciously associated the two events. According to Hoover, Josephus's account regarding Ptolemy IX's installation of Demetrius III in Damascus indicates that the Egyptian monarch did not evacuate Syria after the conclusion of his war with Cleopatra III, or that he perhaps invaded a second time to help Demetrius III following the death of his father. Ptolemy IX probably hoped to use his nephew as an agent in the region; if Demetrius III was installed by his uncle in Damascus in 216 SE (97/96 BC), then Josephus's synchronisation between Ptolemy IX's departure and the death of Antiochus VIII is correct.[44]

- Demetrius III took Antioch before Damascus: Ehling proposed a different reconstruction of events; he contested the dating of Antiochus VIII's death to 96 BC based on Demetrius III's earliest dated coins and argued in favour of 215 SE (98/97 BC) for the former's death and the latter's succession.[30] Ehling's argument agrees with the view of the numismatist Arthur Houghton,[13] who noted that the volume of coins minted by Seleucus VI, the immediate successor of Antiochus VIII, before his takeover of Antioch in 95 BC, surpassed any other mint known from the late Seleucid period.[45] This led Houghton to suggest 98 or 97 BC instead of 96 BC for the death of Antiochus VIII as one year was not enough for Seleucus VI to produce his coins.[46] Hoover rejected the new dating, noting that it was not rare for a king to double his production in a single year during military campaigns, which was the case for Seleucus VI, who was preparing for war against his uncle Antiochus IX.[47] The academic consensus prefers 96 BC for the death of Antiochus VIII.[48]

- Ehling's construction of Demetrius III's early reign has Demetrius III declaring himself king immediately after the death of his father[17] with the help of Ptolemy IX, who, in the view of Ehling, probably supported his nephew with money, troops and ships.[23] Demetrius III landed in Seleucia Pieria, whose inhabitants were known for being Ptolemaic sympathisers, and was crowned king.[35][49] Demetrius III next took Antioch and spent a few weeks in the city before the arrival of Antiochus IX.[17] Demetrius III then marched on Damascus and made it his capital in 97 BC.[35] Ehling's argument is based on coins bearing the epithets Philometor Euergetes, which were attributed by some numismatists to Antioch,[50] but are likely Cilician.[note 6][51] Since all the Damascene coins of Demetrius, which ceased production when the monarch lost his throne, carried dates from 216 SE (97/96 BC) to 225 SE (88/87 BC), and the coins bearing the epithets Philometor Euregetes from Antioch bear no dates, then it is logical, in the view of Ehling, to assume that the Antiochene issues preceded the Damascene one.[52] Ehling explained the change of royal titulary from Philometor Euergetes Callinicus in the north to Theos Philopator Soter in Damascus as a sign of a break between Demetrius III and Ptolemy IX; the Syrian king cast aside the epithet Philometor, which emphasised his mother's Ptolemaic ancestry, and instead invoked his father's heritage by assuming the epithet Philopator.[35] On the other hand, the majority of numismatists date Demetrius III's Antiochene coins to the year 225 SE (88/87 BC).[53][54]

Policy

[edit]

Demetrius III seems to have been content with leaving the struggle against Antiochus IX and his heirs to his brothers; he took advantage of the chaos in the north to consolidate his authority in Damascus.[55] Drawing his legitimacy from his father, he appeared on his coinage with an exaggerated hawked nose in the likeness of Antiochus VIII.[56] Coins from a city named Demetrias, bearing on their reverse a portrait of the Tyche of Damascus, are evidence that Demetrius III might have refounded Damascus and given it the dynastic name Demetrias.[note 7][59][60] Damascene coins mention the city as "holy"; it must have been a privilege bestowed upon it by Demetrius III who possibly also conferred the right of asylum on his capital.[35]

Seleucid kings mostly depicted Greek gods on their coinage,[61] but Demetrius III ruled a contracted realm, where the local cults gained more importance as the Seleucids no longer ruled a heterogeneous kingdom.[62] Local cults came under royal patronage as Seleucid kings attempted to gain the support of their non-Greek subjects.[63] On his royal silver coins from Damascus, the supreme Semitic goddess Atargatis appeared on the reverse,[64] while municipal coins continued to use the portraits of traditional Greek deities.[65] The radiate crown, a sign of divinity,[66] was employed by Demetrius III on some of his coins; this can be an indication that he ritually married Atargatis.[note 8][67] Marrying the supreme goddess indicated that the king considered himself the manifestation of Syria's supreme god and Atargatis' partner, Hadad.[66] The practise was started at an unknown date by Antiochus IV (died 164 BC), the first king to employ the radiate crown, who chose Hierapolis-Bambyce, Atargatis's most important sanctuary, to ritually marry Diana, the manifestation of Atargatis in Syria.[68]

As was typical for a Seleucid king, Demetrius III aimed to acquire as much territory as possible and sought to expand his domains in Syria.[69] The city of Gadara was conquered by Alexander Jannaeus in 100 BC,[70] but the city freed itself and reverted to the Seleucids after the defeat of the Judaean king at the hands of the Nabataeans,[71] an event that happened in 93 BC at the latest.[note 9][72] Gadara was of great strategic importance for Demetrius III as a major military hub for operations in the south; controlling it was vital to the war effort against the Judaeans.[73]

The struggle against Antiochus X

[edit]

In 95 BC, Seleucus VI entered Antioch after defeating and killing Antiochus IX,[74] whose son Antiochus X fled to Aradus and declared himself king.[75] In 94 BC, Seleucus VI was driven out of the capital by Antiochus X;[48] the former escaped to the Cilician city of Mopsuestia where he perished during a local uprising.[76][77] Antiochus XI and Philip I avenged Seleucus VI,[78] and Antiochus XI drove Antiochus X out of the capital in 93 BC.[79][78] Antiochus X was able to regain the city and kill Antiochus XI the same year.[23] In the spring of 93 BC, Demetrius III marched in support of his brother Philip I;[80][75] Demetrius III might have marched north earlier to support Antiochus XI in his final battle.[81]

According to Josephus, Demetrius III and Philip I waged a fierce war against Antiochus X;[75] the language of Josephus indicates that Antiochus X was in a defensive position rather than planning massive campaigns against his cousins.[82] In 220 SE (93/92 BC), no coins were produced for Demetrius III in Damascus; this could mean that he lost control over the city.[83] It is possible that either the Judaeans or the Nabataeans took advantage of Demetrius III's departure to help his brother and occupied the city;[81] the King regained Damascus in 221 SE (92/91 BC).[note 10][84] Antiochus X's date of death is unknown; traditional scholarship, with no evidence, gives the year 92 BC,[83] then has Demetrius taking control of Antioch and ruling it for five years until his downfall in 87 BC.[82] Those traditional dates are hard to justify; using a methodology based on estimating the annual die usage average rate (the Esty formula), Hoover proposed the year 224 SE (89/88 BC) for the end of Antiochus X's reign.[note 11][86] It is estimated that only one to three dies were used by Demetrius III for his Antiochene coins, a number too small to justify a five-year-long reign in Antioch;[82] no literary sources specify the year 92 BC as the date of Demetrius III's occupation of Antioch,[86] and none of his Antiochene coins bear a date.[87]

Judaean campaign

[edit]Following the defeat of Alexander Jannaeus at the hands of the Nabataeans, Judaea was caught in a civil war[72] between the king and a religious group called the Pharisees.[88] According to Josephus, Alexander Jannaeus' opponents persuaded Demetrius III to invade Judaea as it would be conquered easily owing to the civil war.[89] Josephus gave two accounts regarding the numerical strength of Demetrius III; in Antiquities of the Jews, the Syrian king had 3,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry. In the Jewish War, Demetrius III commanded 3,000 cavalry and 14,000 infantry. The latter number is more logical; the number given in Antiquities of the Jews could be an error by a copyist.[90]

The date of the campaign is unclear in Josephus's account.[91] 88 BC is traditionally considered the date of Demetrius III's Judaean campaign, but numismatic evidence shows that coin production increased massively in Damascus in 222 SE (91/90 BC) and 223 SE (90/89 BC).[note 12] This increase indicates that Demetrius was securing the necessary funds for his campaign, making 89 BC more likely as the date of the invasion.[note 13][91] The political situation in Syria in 89 BC helped Demetrius III initiate his invasion of Judaea; Antiochus X was in Antioch while Damascus was firmly in the hands of Demetrius III and there is no indication of a war with his brother Philip I.[note 14][94][95]

The motives of Demetrius III are not specified in Josephus's account;[90] the historian gives the impression that Demetrius III helped the Pharisees free of charge, which is hard to accept. The Syrian king's help must have been conditioned on political concessions by the Jewish rebels.[90] Evidence for Demetrius III's motives is provided by the Pesher Nahum,[96] which reads: [Interpreted, this concerns Deme]trius king of Greece who sought, on the counsel of those who seek smooth things, to enter Jerusalem;[97] the academic consensus identifies "Demetrius king of Greece" with Demetrius III.[note 15][43] The motive leading Demetrius III to attack Judaea might not have had anything to do with the call of the Pharisees. If Alexander Jannaeus took advantage of Demetrius's absence in 93 BC to wrest control of Damascus, then the invasion was probably in retribution against Judaea.[89] It is also possible that Demetrius wanted to take advantage of Judaea's human resources in the struggle against his rivals to the Syrian throne. Finally, the Syrian kings, including Demetrius III's father, never fully accepted the independence of Judaea and entertained plans to reconquer it; the campaign of Demetrius III can be seen in this context.[100]

Demetrius III was the first Seleucid king to set foot in Judaea since Antiochus VII (died 129 BC);[88] according to Josephus, the Syrian king came with his army to the vicinity of Shechem (near Nablus), which he chose as the site for his camp.[note 16] Alexander Jannaeus marched to meet his enemy; Demetrius III tried to persuade Alexander Jannaeus's mercenaries to defect as they were Greeks like him, but the troops did not answer his call. Following this failed attempt, the two kings engaged in battle; Demetrius III lost many troops but decimated Alexander Jannaeus's mercenaries and gained victory.[75] The Judaean king fled to the nearby mountains and according to Josephus, when the 6,000 Judaean rebels in Demetrius III's ranks saw this, they felt pity for their king and deserted Demetrius to join Alexander Jannaeus. At this point, Demetrius III withdrew back to Syria.[102]

The account of Josephus indicates that Demetrius III ended his Judaean campaign because his Jewish allies deserted him, but this is hard to accept; Josephus probably inflated the numbers of Judaeans in the Syrian army, and Demetrius III still had enough soldiers to wage wars in Syria after he departed Judaea. It is more likely that events in Syria forced Demetrius III to conclude his invasion of Judaea.[103] Probably in 88 BC, Antiochus X died while fighting the Parthians, and this must have forced Demetrius III to rush north and fill the power vacuum before Philip I.[103][104] Demetrius III may have feared that his brother would turn on him and try to take Damascus for himself; if it was not for the death of Antiochus X, Demetrius III would probably have conquered Judaea.[103]

Height of power and defeat

[edit]

According to Josephus, following the conclusion of his Judaean campaign, Demetrius III marched on Philip I.[89] During this conflict, which is datable to 225 SE (88/87 BC), soldiers from Antioch were mentioned for the first time in the ranks of Demetrius III, indicating that he took control of the Syrian capital in this year.[note 17][95] No bronze coinage was minted in the name of Demetrius III in Antioch as the city began issuing its own civic bronze coins in 221 SE (92/91 BC); Demetrius III issued silver coins in the Syrian capital as silver coinage remained a royal prerogative.[note 18][83][107] Most of the kingdom came under the authority of Demetrius III; his coins were minted in Antioch, Damascus, Seleucia Pieria and Tarsus.[note 19][43]

According to Josephus, Demetrius III attacked his brother in Beroea with an army of 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry.[103] Philip I's ally, Straton, the tyrant of the city, called on Aziz, an Arab phylarch (tribal leader), and the Parthian governor Mithridates Sinaces for help;[109] the allies' archery drove Demetrius III to take cover in his camp, where he was besieged and eventually surrendered after thirst took its toll on his men.[note 20][102]

Aftermath

[edit]The year of Demetrius III's defeat is most likely 87 BC; the date of Demetrius III's last coin from Damascus is 225 SE (88/87 BC).[105] According to Josephus, Demetrius III was captured and sent to Parthia, where he was treated by the Parthian king with "great honour" until he died of illness. Josephus wrote that the Parthian king was named Mithradates,[102] likely Mithridates III.[111][112] Demetrius III was probably childless;[113] in Damascus, he was succeeded by Antiochus XII, whose first coin was minted in 226 SE (87/86 BC), indicating an immediate succession.[114] Philip I released any captive who was a citizen of Antioch, a step that must have eased his entry into Antioch, which took place soon after the capture of Demetrius III.[109]

Family tree

[edit]| Family tree of Demetrius III |

|---|

Citations:

|

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Ancient sources do not mention the name of Demetrius III's mother, but it is generally assumed by modern scholars that she was Tryphaena, who was mentioned explicitly by Porphyry as the mother of Demetrius III's siblings Antiochus XI and Philip I.[8]

- ^ Some dates in the article are given according to the Seleucid era which is indicated when two years have a slash separating them. Each Seleucid year started in the late autumn of a Gregorian year; thus, a Seleucid year overlaps two Gregorian ones.[12]

- ^ It was customary to name the eldest son after the dynasty's founder Seleucus I, while a younger son would be named Antiochus.[16]

- ^ It is also possible that Demetrius III was claiming to be the saviour of Damascus, protecting it from the Judaeans, Nabataeans and the Itureans.[33]

- ^ Eucaerus also appears in the tables of contents written in the sixth century for the older Greek manuscripts. Those tables are actually summaries of the main text;[36] they sometimes contain discrepancies with the main work.[37]

- ^ The coins Ehling agreed to their Antiochene origin are: a coin with the number 390 in the CSE (Coins of the Seleucid Empire in the Collection of Arthur Houghton) and the number 434 in the SMA (The Seleucid Mint of Antioch) – plus a bronze coin coded CSE 391.[50] The numismatists Houghton, Catherine Lorber and Hoover attributed CSE 390 (SMA 434) to Tarsus,[31] and CSE 391 to Seleucia Pieria; the latter probably had the epithet Callinicus inscribed but some letters are missing due to damage.[33]

- ^ It is not certain that the founder was Demetrius III; it could have been Demetrius II or Antiochus VIII.[57] The historian Alfred Bellinger rejected the identification of a king's portrait on one of Demetrias' coins with Demetrius III or that he refounded it.[58]

- ^ Historian Nicholas L. Wright proposed the hypothesis regarding the connection between the Seleucid radiate crowns and Atargatis. He considered it likely, but difficult to prove, that a radiate crown indicates a ritual marriage between the goddess and a king.[66]

- ^ The Nabataean king Obodas I defeated the Judaeans at some point before 93 BC; this is deduced from the account of Josephus, who stated that following the defeat, Alexander Jannaeus was caught in a civil war that lasted six years. Since this civil war ended only with the intervention of Demetrius III, who lost his throne in 87 BC, then the year 93 BC is the terminus ante quem for the defeat.[72]

- ^ According to Hoover, the account of Josephus regarding the installation of Demetrius III in Damascus by Ptolemy IX following the death of Antiochus XI might actually be a conflation of two actions by the Egyptian king; an initial support in 216 SE (97/96 BC), and a second one in 221 SE (92/91 BC).[81]

- ^ The Esty formula was developed by the mathematician Warren W. Esty; it is a mathematical formula that can calculate the relative number of obverse dies used to produce a certain coin series. The calculation can be used to measure the coin production of a certain king and thus estimate the length of his reign.[85]

- ^ Hoover considered the apparent increase a result of a poor sample coverage, and thus not an actual evidence for an increase in production.[92]

- ^ Coins of Demetrius made of lead, were probably minted during the preparations for the campaign; it is possible that Demetrius III did not have sufficient bronze to mint.[93]

- ^ Historian Edward Dąbrowa preferred the traditional dating; in 88 BC Demetrius III was in control of most of Syria following the death of Antiochus X and had Philip I as his only rival, making him an attractive choice for the Pharisees.[43]

- ^ The historian Isaac Rabinowitz rejected this identification and preferred Demetrius I.[98] The arguments of Rabinowitz were rejected by the historian Hanan Eshel, who noted that Demetrius I controlled Jerusalem, and did not need to seek its entry.[99]

- ^ An interesting find from Khirbat Burnaṭ, near modern Asira ash-Shamaliya, just north of Nablus, is a coin of Demetrius, which are rarely found in Palestine, most of them in the north. The coin from Khirbat Burnaṭ is the only specimen found that far south.[101]

- ^ Ehling considered it possible that the coins from Antioch with the epithets Theos Philopator Soter date to 225 SE (88/87 BC).[105]

- ^ The numismatist Edward Theodore Newell used the traditional date 92 BC for the death of Antiochus X and the start of Demetrius III's reign in Antioch;[83] he believed Demetrius III tried to gain Antioch's loyalty by allowing it to mint its own civic bronze coins.[106]

- ^ The numismatist Joseph Hilarius Eckhel attributed a coin from Sidon to Demetrius III; in fact, this piece belongs to Demetrius II.[108]

- ^ This account is probably taken from Strabo, who in turn might have counted on the work of Posidonius.[110]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Marciak 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Goodman 2005, p. 37.

- ^ a b Kelly 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 76.

- ^ a b Kosmin 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Tinsley 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Otto & Bengtson 1938, pp. 103, 104.

- ^ Bennett 2002, p. note 10.

- ^ Ogden 1999, p. 153.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Grainger 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Biers 1992, p. 13.

- ^ a b Ehling 2008, p. 231.

- ^ Dumitru 2016, p. 261.

- ^ Dumitru 2016, p. 262.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Ehling 2008, p. 234.

- ^ Houghton 1987, p. 81.

- ^ Houghton & Müseler 1990, p. 61.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2016a, p. 10.

- ^ Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 311.

- ^ a b c Ehling 2008, p. 239.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 310.

- ^ Hoschander 1915, p. 651.

- ^ Bevan 2014, p. 56.

- ^ McGing 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Hallo 1996, p. 142.

- ^ Burgess 2004, p. 23.

- ^ a b Ehling 2008, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 587.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 588.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 589.

- ^ Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e f Ehling 2008, p. 240.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 315.

- ^ a b Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 316.

- ^ a b Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 307.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 309.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 335.

- ^ Ehling 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Levenson & Martin 2009, p. 313.

- ^ a b c d Dąbrowa 2011, p. 177.

- ^ Hoover 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Houghton 1989, pp. 97, 98.

- ^ Houghton 1989, p. 98.

- ^ Hoover 2007, p. 286.

- ^ a b Houghton 1989, p. 97.

- ^ Kosmin 2014, p. 133.

- ^ a b Ehling 2008, pp. 233.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, pp. 587, 589.

- ^ Ehling 2008, pp. 232, 233.

- ^ Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 208.

- ^ Lorber & Iossif 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Newell 1939, pp. 82, 83.

- ^ Wright 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Cohen 2006, pp. 244, 244.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 78.

- ^ Cohen 2006, pp. 242, 244.

- ^ Rigsby 1996, p. 511.

- ^ Wright 2010, pp. 193, 199.

- ^ Wright 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Wright 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Ehling 2008, pp. 240, 241.

- ^ a b c Wright 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 74, 78.

- ^ Newell 1939, p. 86.

- ^ Fitzgerald 2004, p. 361.

- ^ Fitzgerald 2004, p. 363.

- ^ a b c Bar-Kochva 1996, p. 138.

- ^ Mittmann 2006, pp. 28, 33.

- ^ Downey 2015, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d Josephus 1833, p. 421.

- ^ Houghton 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, pp. 73, 74.

- ^ a b Houghton 1987, p. 79.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 573.

- ^ Ehling 2008, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Hoover 2007, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d Hoover 2007, p. 290.

- ^ Hoover, Houghton & Veselý 2008, p. 205.

- ^ Hoover 2007, pp. 282–284.

- ^ a b Hoover 2007, p. 294.

- ^ Schürer 1973, p. 135.

- ^ a b Dąbrowa 2011, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Atkinson 2016b, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Dąbrowa 2011, p. 176.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2016a, p. 13.

- ^ Hoover 2011, p. 254.

- ^ Hoover & Iossif 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Atkinson 2016b, p. 47.

- ^ a b Hoover 2007, pp. 294, 295.

- ^ Dąbrowa 2011, pp. 177, 178.

- ^ VanderKam 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Rabinowitz 1978, p. 398.

- ^ Eshel 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Dąbrowa 2011, p. 179.

- ^ Bijovsky 2012, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Josephus 1833, p. 422.

- ^ a b c d Atkinson 2016a, p. 14.

- ^ Hoover 2007, p. 295.

- ^ a b Ehling 2008, p. 245.

- ^ Newell 1917, p. 118.

- ^ Dumitru 2016, p. 267.

- ^ Bellinger 1949, p. 75.

- ^ a b Downey 2015, p. 135.

- ^ Retso 2003, p. 342.

- ^ Simonetta 2001, p. 79.

- ^ Assar 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Hoover 2000, p. 106.

- ^ Houghton 1998, p. 68.

Cited sources

[edit]- Assar, Gholamreza F. (2006). A Revised Parthian Chronology of the Period 91–55 BC. Vol. 8: Papers Presented to David Sellwood. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali. ISBN 978-8-881-47453-0. ISSN 1128-6342.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Atkinson, Kenneth (2016a). "Historical and Chronological Observations on Josephus's Account of Seleucid History in Antiquities 13.365–371: Its Importance for Understanding the Historical Development of the Hasmonean State". Scripta Judaica Cracoviensia. 14. Uniwersytet Jagielloński. ISSN 1733-5760.

- Atkinson, Kenneth (2016b). "Understanding the Relationship Between the Apocalyptic Worldview and Jewish Sectarian Violence: The Case of the War Between Alexander Jannaeus and Demetrius III". In Grabbe, Lester L.; Boccaccini, Gabriele; Zurawski, Jason M. (eds.). The Seleucid and Hasmonean Periods and the Apocalyptic Worldview. The Library of Second Temple Studies. Vol. 88. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-66615-4.

- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (1996). Pseudo Hecataeus, "On the Jews": Legitimizing the Jewish Diaspora. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 21. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26884-5.

- Bellinger, Alfred R. (1949). "The End of the Seleucids". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38. Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. OCLC 4520682.

- Bennett, Christopher J. (2002). "Tryphaena". C. J. Bennett. The Egyptian Royal Genealogy Project hosted by the Tyndale House Website. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Bevan, Edwyn (2014) [1927]. A History of Egypt under the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Routledge Revivals. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-68225-7.

- Biers, William R. (1992). Art, Artefacts and Chronology in Classical Archaeology. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7.

- Bijovsky, Gabriela (2012). "The Coins from Khirbat Burnaṭ (Southwest)". 'Atiqot. 69. Israel Antiquities Authority. ISSN 0792-8424.

- Burgess, Michael Roy (2004). "The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress – The Rise and Fall of Cleopatra II Selene, Seleukid Queen of Syria". The Celator. 18 (3). Kerry K. Wetterstrom. ISSN 1048-0986. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Cohen, Getzel M. (2006). The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 46. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93102-2.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2011). Demetrius III in Judea. Vol. 18. Instytut Historii. Uniwersytet Jagielloński (Department of Ancient History at the Jagiellonian University). ISBN 978-8-323-33053-0. ISSN 1897-3426.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Downey, Robert Emory Glanville (2015) [1961]. A History of Antioch in Syria from Seleucus to the Arab Conquest. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-400-87773-7.

- Dumitru, Adrian (2016). "Kleopatra Selene: A Look at the Moon and Her Bright Side". In Coşkun, Altay; McAuley, Alex (eds.). Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Historia – Einzelschriften. Vol. 240. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-11295-6. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Ehling, Kay (2008). Untersuchungen Zur Geschichte Der Späten Seleukiden (164–63 v. Chr.) Vom Tode Antiochos IV. Bis Zur Einrichtung Der Provinz Syria Unter Pompeius. Historia – Einzelschriften (in German). Vol. 196. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-09035-3. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Eshel, Hanan (2008). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Vol. 9. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing and Yad Ben-Zvi Press. ISBN 978-0-802-86285-3.

- Fitzgerald, John Thomas (2004). "Gadara: Philodemus' Native City". In Fitzgerald, John Thomas; Obbink, Dirk D.; Holland, Glenn Stanfield (eds.). Philodemus and the New Testament World. Supplements to Novum Testamentum. Vol. 111. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-11460-9. ISSN 0167-9732.

- Goodman, Martin (2005) [2002]. "Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period". In Goodman, Martin; Cohen, Jeremy; Sorkin, David Jan (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-28032-2.

- Grainger, John D. (1997). A Seleukid Prosopography and Gazetteer. Mnemosyne, Bibliotheca Classica Batava. Supplementum. Vol. 172. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-10799-1. ISSN 0169-8958.

- Hallo, William W. (1996). Origins. The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 6. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10328-3. ISSN 0169-9024.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2000). "A Dedication to Aphrodite Epekoos for Demetrius I Soter and his Family". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 131. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH. ISSN 0084-5388.

- Hoover, Oliver (2006). "A Late Hellenistic Lead Coinage from Gaza". Israel Numismatic Research. 1. The Israel Numismatic Society. ISSN 1565-8449.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2007). "A Revised Chronology for the Late Seleucids at Antioch (121/0–64 BC)". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 56 (3). Franz Steiner Verlag: 280–301. doi:10.25162/historia-2007-0021. ISSN 0018-2311. S2CID 159573100.

- Hoover, Oliver D.; Houghton, Arthur; Veselý, Petr (2008). The Silver Mint of Damascus under Demetrius III and Antiochus XII (97/6 BC–83/2 BC). second. Vol. 20. American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-89722-305-8. ISSN 1053-8356.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Hoover, Oliver D.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "A Lead Tetradrachm of Tyre from the Second Reign of Demetrius II". The Numismatic Chronicle. 169. Royal Numismatic Society. ISSN 0078-2696.

- Hoover, Oliver D. (2011). "A Second Look at Production Quantification and Chronology in the Late Seleucid Period". In de Callataÿ, François (ed.). Time is Money? Quantifying Mmonetary Supplies in Greco-Roman Times. Pragmateiai. Vol. 19. Edipuglia. pp. 251–266. ISBN 978-8-872-28599-2. ISSN 2531-5390.

- Hoschander, Jacob (1915). "Review: Recent Assyro-Babylonian Literature". The Jewish Quarterly Review. new series. 5 (4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 615–661. doi:10.2307/1451298. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1451298.

- Houghton, Arthur (1987). "The Double Portrait Coins of Antiochus XI and Philip I: a Seleucid Mint at Beroea?". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. 66. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur (1989). "The Royal Seleucid Mint of Seleucia on the Calycadnus". In Le Rider, Georges Charles; Jenkins, Kenneth; Waggoner, Nancy; Westermark, Ulla (eds.). Kraay-Mørkholm Essays. Numismatic Studies in Memory of C.M. Kraay and O. Mørkholm. Numismatica Lovaniensia. Vol. 10. Université Catholique de Louvain: Institut Supérieur d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de l'Art. Séminaire de Numismatique Marcel Hoc. OCLC 910216765.

- Houghton, Arthur; Müseler, Wilhelm (1990). "The Reigns of Antiochus VIII and Antiochus IX at Damascus". Schweizer Münzblätter. 40 (159). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. ISSN 0016-5565.

- Houghton, Arthur (1998). "The Struggle for the Seleucid Succession, 94–92 BC: a New Tetradrachm of Antiochus XI and Philip I of Antioch". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. 77. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Houghton, Arthur; Lorber, Catherine; Hoover, Oliver D. (2008). Seleucid Coins, A Comprehensive Guide: Part 2, Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. Vol. 1. The American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-980-23872-3.

- Josephus (1833) [c. 94]. Burder, Samuel (ed.). The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish Historian. Translated by Whiston, William. Kimber & Sharpless. OCLC 970897884.

- Kelly, Douglas (2016). "Alexander II Zabinas (Reigned 128–122)". In Phang, Sara E.; Spence, Iain; Kelly, Douglas; Londey, Peter (eds.). Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia (3 Vols.). Vol. I. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-610-69020-1.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Levenson, David B.; Martin, Thomas R. (2009). "Akairos or Eukairos? The Nickname of the Seleucid King Demetrius III in the Transmission of the Texts of Josephus' War and Antiquities". Journal for the Study of Judaism. 40 (3). Brill. ISSN 0047-2212.

- Lorber, Catharine C.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "Seleucid Campaign Beards". L'Antiquité Classique. 78. L'asbl L'Antiquité Classique. ISSN 0770-2817.

- Marciak, Michał (2017). Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene. Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West. Impact of Empire. Vol. 26. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-35070-0. ISSN 1572-0500.

- McGing, Brian C. (2010). Polybius' Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-71867-2.

- Mittmann, Siegfried (2006). "Die Hellenistische Mauerinschrift von Gadara (Umm Qēs) und die Seleukidisch Dynastische Toponymie Palästinas". Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages (in German). 32 (2). Department of Ancient Studies: Stellenbosch University. ISSN 0259-0131.

- Newell, Edward Theodore (1917). "The Seleucid Mint of Antioch". American Journal of Numismatics. 51. American Numismatic Society. ISSN 2381-4594.

- Newell, Edward Theodore (1939). Late Seleucid Mints in Ake-Ptolemais and Damascus. Numismatic Notes & Monographs. Vol. 84. American Numismatic Society. OCLC 2461409.

- Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-715-62930-7.

- Otto, Walter Gustav Albrecht; Bengtson, Hermann (1938). Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches: ein Beitrag zur Regierungszeit des 8. und des 9. Ptolemäers. Abhandlungen (Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse) (in German). Vol. 17. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 470076298.

- Rabinowitz, Isaac (1978). "The Meaning of the Key ("Demetrius") – Passage of the Qumran Nahum-Pesher". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 98 (4). American Oriental Society: 394–399. doi:10.2307/599751. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 599751.

- Retso, Jan (2003). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-1-136-87282-2.

- Rigsby, Kent J. (1996). Asylia: Territorial Inviolability in the Hellenistic World. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 22. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20098-2.

- Schürer, Emil (1973) [1874]. Vermes, Geza; Millar, Fergus; Black, Matthew (eds.). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. Vol. I (2014 ed.). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-1-472-55827-5.

- Simonetta, Alberto M. (2001). "A Proposed Revision of the Attributions of the Parthian Coins Struck during the So-called 'Dark Age' and Its Historical Significance". East and West. 51 (1/2). Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO). ISSN 0012-8376.

- Taylor, Michael J. (2013). Antiochus the Great. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-848-84463-6.

- Tinsley, Barbara Sher (2006). Reconstructing Western Civilization: Irreverent Essays on Antiquity. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-1-575-91095-6.

- VanderKam, James C. (2012). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-802-86679-0.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2005). "Seleucid Royal Cult, Indigenous Religious Traditions and Radiate Crowns: The Numismatic Evidence". Mediterranean Archaeology. 18. Sydney University Press. ISSN 1030-8482.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2010). "Non-Greek Religious Iconography on the Coinage of Seleucid Syria". Mediterranean Archaeology. 22/23. Sydney University Press. ISSN 1030-8482.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2011). "The Iconography of Succession Under the Late Seleukids". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. The Numismatic Association of Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2012). Divine Kings and Sacred Spaces: Power and Religion in Hellenistic Syria (301-64 BC). British Archaeological Reports (BAR) International Series. Vol. 2450. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-407-31054-1.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VII (9th ed.). 1878. p. 58.

- The biography of Demetrius III Archived 5 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine in the website of the numismatist Petr Veselý.