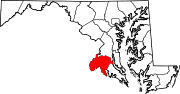

Charles County, Maryland

Charles County | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within the U.S. state of Maryland | |

Maryland's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 38°29′N 77°01′W / 38.48°N 77.01°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | April 13, 1658 |

| Named for | Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore |

| Seat | La Plata |

| Largest community | Waldorf |

| Area | |

• Total | 643 sq mi (1,670 km2) |

| • Land | 458 sq mi (1,190 km2) |

| • Water | 185 sq mi (480 km2) 29% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 166,617 |

| • Density | 363.8/sq mi (140.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 5th |

| Website | www |

Charles County is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 census, the population was 166,617.[1] The county seat is La Plata.[2] The county was named for Charles Calvert (1637–1715), third Baron Baltimore. The county is part of the Southern Maryland region of the state.[3]

With a median household income of $103,678,[4] Charles County is the 39th-wealthiest county in the United States as of 2020, and the highest-income county in the United States with a Black-majority population.[5]

History

[edit]Charles County was created in 1658 by an Order in Council. There was also an earlier Charles County from 1650 to 1654, sometimes referred to in historic documents as Old Charles County,[6][7][8] which consisted largely of lands within today's borders but "included parts of St. Mary’s, Calvert, present-day Charles, and Prince George’s County".[9] John Tayloe I purchased land around Nanjemoy Creek after 1710 from which to mine iron and ship to his furnaces at Bristol Iron Works, Neabsco Iron Works and later Occoquan Ironworks.

In April 1865, John Wilkes Booth made his escape through Charles County after shooting President Abraham Lincoln. He was on his way to Virginia. He stopped briefly in Waldorf (then called Beantown) and had his broken leg set by local Doctor Samuel Mudd, who was later sent to prison for helping him.[10] Booth then proceeded to hide in the Zekiah Swamp in Charles County, avoiding search parties for over a week until he and his accomplice were able to successfully cross the Potomac River.[10]

The 1911 Digges Amendment, which attempted to disenfranchise African Americans in Maryland, was drafted by Democratic state delegate (lower house) Walter Digges and co-sponsored by state senator (upper house) William J. Frere, both from Charles County, Maryland. In Maryland's unrestricted general election of 1911, the Digges Amendment was defeated with 46,220 votes for and 83,920 votes against the proposal. Nationally Maryland citizens achieved the most notable rejection of a black-disfranchising amendment.[11]

In 1926, a tornado ripped through the county leaving 17 dead (including 13 schoolchildren). On April 28, 2002, another tornado (rated an F-4) destroyed much of downtown La Plata killing 3 and injuring over 100 people.[12]

The county has numerous properties on the National Register of Historic Places.[13] Among them are Green Park and Pleasant Hill, home of the Green and Spalding Families.

On December 4, 2004, an arson took place in the development of Hunters Brooke, a few miles southeast of Indian Head. The Hunters Brooke Arson was the largest residential arson[14] in Maryland history.[15][16][17]

Politics and government

[edit]Owing to the considerable voting power of its large number of freedmen following the Civil War,[18] and later its growth as a suburban area, Charles County was for a long time solidly Republican. The only Democrat to carry Charles County until 1960 was Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, although Alf Landon and Wendell Willkie defeated Roosevelt in the next two elections by a combined margin of just 50 votes. Since the turn of the millennium, Charles County has become reliably Democratic, although not as overwhelmingly so as other parts of Maryland's Washington, D.C. suburbs.[19] Charles County is one of only two counties in the nation to have voted for Al Gore in 2000 after voting for Bob Dole in 1996, along with Orange County, Florida.[20]

Voter registration

[edit]| Voter registration and party enrollment as of March 2024[21] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | 74,828 | 60.43% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 24,372 | 19.68% | |||

| Republican | 22,962 | 18.54% | |||

| Libertarian | 441 | 0.36% | |||

| Other parties | 1,218 | 0.98% | |||

| Total | 123,821 | 100% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 26,145 | 28.39% | 63,454 | 68.90% | 2,498 | 2.71% |

| 2020 | 25,579 | 28.58% | 62,171 | 69.47% | 1,748 | 1.95% |

| 2016 | 25,614 | 32.71% | 49,341 | 63.01% | 3,348 | 4.28% |

| 2012 | 25,178 | 33.47% | 48,774 | 64.84% | 1,270 | 1.69% |

| 2008 | 25,732 | 36.69% | 43,635 | 62.22% | 760 | 1.08% |

| 2004 | 28,442 | 48.84% | 29,354 | 50.40% | 445 | 0.76% |

| 2000 | 21,768 | 48.82% | 21,873 | 49.05% | 951 | 2.13% |

| 1996 | 17,432 | 48.66% | 15,890 | 44.36% | 2,501 | 6.98% |

| 1992 | 17,293 | 44.97% | 14,498 | 37.70% | 6,663 | 17.33% |

| 1988 | 20,828 | 63.57% | 11,823 | 36.09% | 113 | 0.34% |

| 1984 | 16,132 | 60.97% | 10,264 | 38.79% | 64 | 0.24% |

| 1980 | 11,807 | 53.62% | 8,887 | 40.36% | 1,326 | 6.02% |

| 1976 | 7,792 | 45.00% | 9,525 | 55.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1972 | 9,665 | 67.34% | 4,502 | 31.37% | 186 | 1.30% |

| 1968 | 4,645 | 38.50% | 4,247 | 35.20% | 3,173 | 26.30% |

| 1964 | 3,455 | 34.55% | 6,546 | 65.45% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 4,560 | 45.41% | 5,482 | 54.59% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 5,088 | 56.41% | 3,931 | 43.59% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 4,334 | 56.13% | 3,338 | 43.23% | 49 | 0.63% |

| 1948 | 2,703 | 58.49% | 1,878 | 40.64% | 40 | 0.87% |

| 1944 | 2,755 | 59.50% | 1,875 | 40.50% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 2,716 | 49.71% | 2,692 | 49.27% | 56 | 1.02% |

| 1936 | 2,623 | 49.64% | 2,597 | 49.15% | 64 | 1.21% |

| 1932 | 1,851 | 42.35% | 2,473 | 56.58% | 47 | 1.08% |

| 1928 | 2,522 | 57.44% | 1,860 | 42.36% | 9 | 0.20% |

| 1924 | 2,215 | 56.59% | 1,491 | 38.09% | 208 | 5.31% |

| 1920 | 2,585 | 60.54% | 1,642 | 38.45% | 43 | 1.01% |

| 1916 | 1,374 | 48.06% | 1,363 | 47.67% | 122 | 4.27% |

| 1912 | 1,573 | 59.45% | 918 | 34.69% | 155 | 5.86% |

| 1908 | 1,643 | 57.23% | 1,167 | 40.65% | 61 | 2.12% |

| 1904 | 1,659 | 57.80% | 1,180 | 41.11% | 31 | 1.08% |

| 1900 | 2,268 | 61.93% | 1,368 | 37.36% | 26 | 0.71% |

| 1896 | 2,117 | 59.99% | 1,372 | 38.88% | 40 | 1.13% |

| 1892 | 1,279 | 53.49% | 1,051 | 43.96% | 61 | 2.55% |

Board of Commissioners

[edit]Charles County is governed by county commissioners, the traditional form of county government in Maryland. There are five commissioners. As of 2022[update], they are:

| Position | Name | Affiliation | District | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| President | Reuben Collins | Democratic | At-Large | |

| Commissioner | Gilbert Bowling | Democratic | District 1 | |

| Commissioner | Thomasina Coates | Democratic | District 2 | |

| Commissioner | Amanda Stewart | Democratic | District 3 | |

| Commissioner | Ralph Patterson | Democratic | District 4 | |

Charles County is entirely within the 5th Congressional District, which also includes Calvert, St. Mary's, and parts of Anne Arundel and Prince George's counties. The current representative is former Democratic House Majority Leader and former House Minority Whip Steny H. Hoyer.

Geography

[edit]According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has an area of 643 square miles (1,670 km2), of which 458 square miles (1,190 km2) is land and 185 square miles (480 km2) (29%) water.[24]

In its western wing, along the southernmost bend in Maryland Route 224, Charles County contains a place due north, east, south, and west of the same state—Virginia.[25]

Adjacent counties

[edit]- Prince George's County (north)

- Fairfax County, Virginia (northwest)

- Calvert County (east)

- Stafford County, Virginia (west)

- Prince William County, Virginia (west)

- St. Mary's County (southeast)

- Westmoreland County, Virginia (southeast)

- King George County, Virginia (south)

National protected area

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 20,613 | — | |

| 1800 | 19,172 | −7.0% | |

| 1810 | 20,245 | 5.6% | |

| 1820 | 16,500 | −18.5% | |

| 1830 | 17,769 | 7.7% | |

| 1840 | 16,023 | −9.8% | |

| 1850 | 16,162 | 0.9% | |

| 1860 | 16,517 | 2.2% | |

| 1870 | 15,738 | −4.7% | |

| 1880 | 18,548 | 17.9% | |

| 1890 | 15,191 | −18.1% | |

| 1900 | 17,662 | 16.3% | |

| 1910 | 16,386 | −7.2% | |

| 1920 | 17,705 | 8.0% | |

| 1930 | 16,166 | −8.7% | |

| 1940 | 17,612 | 8.9% | |

| 1950 | 23,415 | 32.9% | |

| 1960 | 32,572 | 39.1% | |

| 1970 | 47,678 | 46.4% | |

| 1980 | 72,751 | 52.6% | |

| 1990 | 101,154 | 39.0% | |

| 2000 | 120,546 | 19.2% | |

| 2010 | 146,551 | 21.6% | |

| 2020 | 166,617 | 13.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 171,973 | [26] | 3.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] 1790-1960[28] 1900-1990[29] 1990-2000[30] 2010[31] 2020[32] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[33] | Pop 2010[31] | Pop 2020[32] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 81,111 | 70,905 | 56,832 | 67.29% | 48.38% | 34.11% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 31,203 | 59,201 | 80,850 | 25.88% | 40.40% | 48.52% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 858 | 877 | 995 | 0.71% | 0.60% | 0.60% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 2,169 | 4,296 | 5,624 | 1.80% | 2.93% | 3.38% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 66 | 87 | 147 | 0.05% | 0.06% | 0.09% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 199 | 243 | 957 | 0.17% | 0.17% | 0.57% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,218 | 4,683 | 9,535 | 1.84% | 3.20% | 5.72% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,722 | 6,259 | 11,677 | 2.26% | 4.27% | 7.01% |

| Total | 120,546 | 146,551 | 166,617 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 146,551 people, 51,214 households, and 38,614 families residing in the county.[34] The population density was 320.2 inhabitants per square mile (123.6/km2). There were 54,963 housing units at an average density of 120.1 per square mile (46.4/km2).[35] The racial makeup of the county was 50.3% white, 41.0% black or African American, 3.0% Asian, 0.7% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 1.3% from other races, and 3.7% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 4.3% of the population.[34] In terms of ancestry, 12.6% were German, 10.8% were Irish, 8.7% were English, 6.3% were American, and 5.1% were Italian.[36]

Of the 51,214 households, 41.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.2% were married couples living together, 16.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 24.6% were non-families, and 19.8% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.83 and the average family size was 3.24. The median age was 37.4 years.[34]

The median income for a household in the county was $88,825 and the median income for a family was $98,560. Males had a median income of $62,210 versus $52,477 for females. The per capita income for the county was $35,780. About 3.7% of families and 5.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.8% of those under age 18 and 4.6% of those age 65 or over.[37]

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[38] of 2000, there were 120,546 people, 41,668 households, and 32,292 families residing in the county. The population density was 262 inhabitants per square mile (101/km2). There were 43,903 housing units at an average density of 95 per square mile (37/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 68.51% White, 26.06% Black or African American, 0.75% Native American, 1.82% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.72% from other races, and 2.08% from two or more races. 2.26% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 11.6% were of German, 10.8% Irish, 10.2% English, 9.3% American and 5.3% Italian ancestry.

There were 41,668 households, out of which 41.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.00% were married couples living together, 14.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 22.50% were non-families. 17.20% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.86 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 28.70% under the age of 18, 7.60% from 18 to 24, 33.20% from 25 to 44, 22.70% from 45 to 64, and 7.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.20 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $62,199, and the median income for a family was $67,602 (these figures had risen to $80,573 and $89,358 respectively as of a 2007 estimate). Males had a median income of $43,371 versus $34,231 for females. The per capita income for the county was $24,285. About 3.70% of families and 5.50% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.70% of those under age 18 and 8.60% of those age 65 or over.

As of 2010, the county population's racial makeup was 48.38% Non-Hispanic whites, 40.96% blacks, 0.65% Native Americans, 2.98% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islanders, 0.17% Non-Hispanics of some other race, 3.20% Non-Hispanics reporting more than one race and 4.27% Hispanic.

Economy

[edit]Top employers

[edit]According to the 2022 publication "Meet Charles County" of the County Department of Economic Development, its top employers are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Naval Surface Warfare Center / Naval Support Facility Indian Head | 3,834 |

| 2 | Charles County Public Schools / Board of Education | 3,701 |

| 3 | Charles County Government | 1,814 |

| 4 | University of Maryland Charles Regional Medical Center | 775 |

| 5 | Walmart / Sam's Club | 637 |

| 6 | College of Southern Maryland | 602 |

| 7 | Waldorf Chevy/Cadillac, Ford, Toyota/Scion, Dodge | 583 |

| 8 | Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative (SMECO) | 471 |

| 9 | Safeway | 465 |

| 10 | Target | 465 |

| 11 | The Wills Group | 344 |

| 12 | Lowe's | 332 |

| 13 | Chick-fil-A | 294 |

| 14 | ADJ Sheet Metal | 280 |

| 15 | Restore Health Rehabilitation, La Plata Center | 260 |

| 16 | Sagepoint Senior Living Services | 250 |

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Charles County is served by numerous state highways and one U.S. Highway:

Major highways

[edit]Communities

[edit]Towns

[edit]- Indian Head

- La Plata (county seat)

- Port Tobacco Village

Census-designated places

[edit]The Census Bureau recognizes the following census-designated places in the county:

Unincorporated communities

[edit]Notable people

[edit]Colonial and Revolutionary Periods

[edit]- Charles Brooke (1636–1671) English immigrant & first Southerner to graduate from Harvard College, Class of 1655; Sheriff, Calvert County 1665[40]

- Gustavus Richard Brown (1747–1804) Edinburgh-educated doctor; served in Revolutionary War; physician to George Washington, attended his death

- James Craik (1727–1814) Scottish immigrant; Physician General of the Continental Army; friend & physician to George Washington, attended his death

- John Hanson (1721–1783) born Port Tobacco; Founding Father of United States; Signer, Articles of Confederation; President, Confederation Congress

- Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer (1723–1790) born Port Tobacco; Founding Father of U.S.; Delegate, Constitutional Convention; Signer, U.S. Constitution

- Capt. James Neale (1615–1684) born in London, immigrated around 1635; Member, Maryland Council; founded Wollaston Manor & Cobb Island

- Leonard Neale (1746–1817) born Port Tobacco; Jesuit President of Georgetown; Archbishop of Baltimore; first U.S.-consecrated Catholic prelate (1800)

- William Smallwood (1732–1792) Officer, Provincial Troops; Major General, 1st Maryland Regiment of the Continental Army; Governor of Maryland[41]

- Benjamin Stoddert (1751–1813) Captain of Cavalry in the Continental Army; first U.S. Secretary of the Navy in the John Adams administration

- Thomas Stone (1743–1787) born at Poynton Manor near Port Tobacco; Founding Father of the United States; Signer, U.S. Declaration of Independence

- Andrew White (1579–1656) born in London; Jesuit with first colonists arriving on Ark & Dove; established mission to the Potapoco at Chapel Point (1641)

19th century

[edit]- George Cary (1789–1843) born near Allen's Fresh; practiced law in Frederick; moved to Appling County, Georgia; Member, U.S. House 1823-27[42]

- Barnes Compton (1830–1898) born Port Tobacco, Princeton '51; Pres., Maryland Senate; Treasurer of Maryland; Member, U.S. House 1885–90, 91-94[43]

- Josiah Henson (1789–1883) born into slavery in Port Tobacco; escaped to Canada & founded community of fugitive slaves; author, abolitionist & minister

- Jane Herbert Wilkinson Long (1798–1880) born Charles County; Texas Patriot & boarding-house matron; dubbed "Mother of Texas" by Sam Houston

- Samuel A. Mudd (1833–1883) born near Bryantown; physician imprisoned for aiding John Wilkes Booth after assassination of Pres. Abraham Lincoln

- Sydney E. Mudd (1858–1911) born in Gallant Green; Speaker, Maryland House of Delegates; Member, U.S. House of Reps 1890–91, 1897-1911[44]

- Francis Neale (1756–1836) born Port Tobacco; Jesuit pastor of St. Thomas Manor & Holy Trinity, first Catholic Church in D.C., President of Georgetown

- Raphael Semmes (1809–1877) born near Nanjemoy; US Navy officer; Captain, CSS Sumter & CSS Alabama; Rear Admiral, Confederate States Navy[45]

20th & 21st centuries

[edit]- Chuck Brown (1936–2012) "Godfather of Go-Go", a subgenre of funk that evolved in the D.C. area in the 1970s; lived in Brandywine

- Danny Gatton (1945–1994) Virtuoso guitarist; created a jazz fusion musical style he called "redneck jazz"; lived in Newburg, died by suicide

- Matthew Henson (1866–1955) born in Nanjemoy; African-American explorer; first to reach North Pole in 1909, with Robert Peary & 4 Inuit companions

- Larry Johnson (born 1979) from Pomfret; former NFL running back; played for K.C. Chiefs, Cincinnati Bengals, Washington Redskins & Miami Dolphins

- Shawn Lemon (born 1988) Attended Westlake H.S. in Waldorf; played with seven teams in the Canadian Football League as a defensive lineman

- Joel & Benji Madden (born 1979) Identical twins from Waldorf; both with bands The Madden Brothers & Good Charlotte; Benji married to Cameron Diaz

- Christina Milian (born 1981) Movie & TV actress; Top 40 singer/songwriter in US (Top 4 in UK); raised in Waldorf to age 13 & part of high school

- Randy Starks (born 1983) Attended Westlake in Waldorf; played NFL as a defensive end with Tennessee Titans, Miami Dolphins & Cleveland Browns

- Robert Stethem (1961–1985) U.S. Navy diver; murdered in Beirut during hijacking of TWA Flight 847; grew up in Pinefield community of Waldorf

- Turkey Tayac (1895–1978) born Charles County; Chief, one branch of Piscataway Indian Nation; WWI veteran; Medicine Man & Native American activist

- Angela Renée White a.k.a. "Blac Chyna" (born 1988) Model, socialite & television personality; attended Henry E. Lackey High School in Indian Head[46]

Sports

[edit]| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Maryland Blue Crabs | ALPB, Baseball | Regency Furniture Stadium | 2008 | 0 |

See also

[edit]- Carpenter Point, Charles County, Maryland

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Charles County, Maryland

References

[edit]- ^ "Charles County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Maryland. com Staff. "Southern Maryland". Maryland.com. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Charles County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Wilkins, Tracee (July 7, 2022). "Charles County Surpasses Prince George's as Wealthiest Black County in US: Post". NBC Washington. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "The Counties of Maryland". 630. The Archives of Maryland Online: 122–124. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Maryland Geological Survey (1911). "Prince George's County". The Johns Hopkins Press: 21–22. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Maryland Geological Survey (1906). "Maryland Geological Survey: General Reports". The Johns Hopkins Press: 474–477. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Klapthor, Margaret Brown; Brown, Paul Dennis (2013). History of Charles County, Maryland, Written In Its Tercentenary Year of 1958 (Heritage Classic paperback ed.). Heritage Books, Inc. p. back cover. ISBN 978-0788401602.

- ^ a b "The Assassin's Escape: Following John Wilkes Booth". National Park Service. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ STEPHEN TUCK, "Democratization and the Disfranchisement of African Americans in the US South during the Late 19th Century" (pdf) Archived February 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Spring 2013, reading for "Challenges of Democratization", by Brandon Kendhammer, Ohio University

- ^ "An account of deadly 1926 La Plata tornado". Baltimore Sun. November 19, 2009.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ United States Attorney for the District of Maryland (March 1, 2006). "Violent Crime Program 2005 Annual Report" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Courson, Paul; Joanthan Wild (December 21, 2004). "Two more arrested in Maryland fires". Washington, Dc: CNN. p. 1. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Witte, Brian (January 3, 2005). "Maryland Hunts for Motives Behind State's Largest Residential Arson". Insurance Journal. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Hancock, David (December 18, 2004). "3 More Charged In Maryland Arson". CBS NEWS. LA PLATA, Md. p. 1. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Levine, Mark V.; ‘Standing Political Decisions and Critical Realignment: The Pattern of Maryland Politics, 1872-1948’; The Journal of Politics, volume 38, no. 2 (May 1976), pp. 292-325

- ^ "JOSH KURTZ: FORGET PRINCE GEORGE'S – CHECK OUT KING CHARLES FOR POLITICAL INTRIGUE". Center Maryland. June 2, 2014. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ "The 2016 Streak Breakers". Sabato Crystal Ball. October 6, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ "Maryland Board of Elections Voter Registration Activity Report March 2024" (PDF). Maryland Board of Elections. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ "Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ This oddity of political geography happens in other places in Maryland.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decades". US Census Bureau.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Charles County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Charles County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Charles County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b c "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Grayton Populated Place Profile / Charles County, Maryland Data".

- ^ Morison, Samual Eliot (January 1933). "Virginians and Marylanders at Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century". William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine. 13 (1): 2–9. doi:10.2307/1922830. JSTOR 1922830. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

Mr. [Charles] Brooke of Harvard was one of the sons of Robert Brooke of Whitechurch, Hampshire, a graduate of Wadham College, Oxford (B.A. 1620, M.S. 1624), and a wealthy and prominent planter of Charles County, Maryland… [After] arrival of the Brooke family in Maryland, Mr. Brooke entered Harvard College June 3, 1651.

- ^ "William Smallwood (1732-1792)". msa.maryland.gov. Biographical Series. Annapolis: Maryland State Archives. December 20, 2002.

Although Smallwood 'waited on Washington and urged the Necessity of attending [his] Troops,' Washington 'refused to discharge' them… Smallwood was therefore absent during the early portions of the Battle of Brooklyn on August 27, 1776. British soldiers outflanked the American soldiers under [Major Mordecai] Gist's command in a surprise attack. The Marylanders retreated, fighting their way toward the Gowanus Creek… Smallwood arrived later in the battle and provided covering fire for the retreating American soldiers with two cannons and some reinforcements… and subsequently faced a deadly British onslaught. The Marylanders led several charges against the British, holding them at bay for a crucial period of time that saved Washington's army… On October 28, 1776… in the Battle of White Plains, [Gen.] Smallwood's soldiers once again saved Washington's army… Positioned on Chatterton's Hill, the Marylanders charged British soldiers, pushing them back briefly. A series of British counterattacks forced the Marylanders to retreat, but prevented the destruction of the entire Continental Army. The 1st Maryland Regiment suffered greatly in the battle. Smallwood himself received two 'slight' wounds during the orderly retreat, receiving one in his wrist and another in his hip.

- ^ "Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896". Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Barnes Compton (1830-1898)". msa.maryland.gov. Biographical Series. Annapolis: Maryland State Archives. August 6, 2008.

- ^ "MUDD, Sydney Emanuel (1858-1911)". bioguide.congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington D.C.: U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

Successfully contested as a Republican the election of Barnes Compton to the Fifty-first Congress and served from March 20, 1890, to March 3, 1891; unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1890 to the Fifty-second Congress; elected to the State house of delegates in 1895 and served as speaker… elected to the Fifty-fifth and to the six succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1897-March 3, 1911).

- ^ "Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes, Confederate States Navy, (1809-1877)". The Navy Department Library (online). Washington D.C.: Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

Semmes was… given command of the newly-built cruiser CSS Alabama. From August 1862 until June 1864, Semmes took his ship through the Atlantic, into the Gulf of Mexico, around the Cape of Good Hope and into the East Indies, capturing some sixty merchantmen and sinking one Federal warship, USS Hatteras. At the end of her long cruise, Alabama was blockaded at Cherbourg, France, while seeking repairs. On June 19, 1864, Semmes took her to sea to fight the Union cruiser USS Kearsarge and was wounded when she was sunk in action. Rescued by the British yacht Dearhound, he went to England, recovered and made his way back to the Confederacy.

- ^ "Blac Chyna - Before She Was Famous - Michael McCrudden". Michael McCrudden. May 11, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Charles County at the Wayback Machine (archived June 1, 2012)